Torture by Design: Saying No to the Architecture of Solitary Confinement and Cruelty

–An interview with Raphael Sperry

By Angola 3 News

Friday, August 16 marked the 40th consecutive day of a multi-ethnic statewide prisoner hunger strike initiated from inside the Security Housing Unit (SHU) of California’s Pelican Bay State Prison. When the strike first began on July 8, the ‘California Department of Corrections and Reform’ (CDCR) reported 30,000 participants statewide, which the Los Angeles Times wrote “could be the largest prison protest in state history.” In response, the hunger strikers have been shown support from around the world (watch our videos from Oakland, CA).

This week, as the striking prisoners’ health continued to worsen, the families of prisoners and supporters gathered on the steps of the State Capitol building in Sacramento, and over 120 health professionals called “upon Governor Jerry Brown and Jeffrey Beard, Secretary of the CDCR, to immediately enter into good-faith negotiations with the prisoner representatives, and to respond to their demands, in order to end this crisis before lives are lost.”

The current hunger strike follows on the heels of a similar 2011 strike that was also initiated from the Pelican Bay SHU, with the same five demands. Further illustrating the scandalous nature of California’s prison system, this month the US Supreme Court ruling once again that 10,000 prisoners must be removed from state prisons, and documentation has emerged of widespread sterilization of California’s female prisoners.

As the horror of solitary confinement comes under increasing scrutiny in the US and around the world, human rights activists are confronting this public health and safety epidemic from a variety of angles. One group, called Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) has challenged solitary confinement in US prisons by recently launching a Change.org petition “asking the American Institute of Architects (AIA, the mainstream professional association for architects) to amend its Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct to prohibit the design of spaces for killing, torture, and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. In the United States, this comprises the design of execution chambers and super-maximum security prisons (‘supermax’), where solitary confinement is an intolerable form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. As people of conscience and as a profession dedicated to improving the built environment for all people, we cannot participate in the design of spaces that violate human life and dignity. Participating in the development of buildings designed for killing, torture, or cruel, inhuman or degrading is fundamentally incompatible with professional practice that respects standards of decency and human rights. AIA has the opportunity to lead our profession in upholding human rights.”

In this interview, we speak with Raphael Sperry, an architect and President of Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR). He is a Soros Justice Fellow and advocates for architects to engage with issues of human rights in the built environment, especially in U.S. prisons. He has participated in the design of airports, office towers, and private homes among other building types, and has taught architecture at Stanford Univeristy and California College of the Arts in San Francisco.

Angola 3 News: For years now, CA prison authorities have cited alleged ‘gang’ affiliations as the official reason for so many prisoners’ placement in prolonged solitary confinement. Recently, CDCR authorities have publicly claimed that the ongoing CA prison hunger strike is a ‘gang conspiracy.’ What do you think of the authorities’ continuing refusal to acknowledge that the hunger strikers’ demands have even a hint of legitimacy?

Raphael Sperry: It’s simply ridiculous to ignore the problems that CDCR has caused with the conditions in their solitary units, and fear-mongering about gangs is not a response. Even if the hunger strikers were gang leaders, they would still be entitled to human rights.

But I’d actually like to see CDCR take some responsibility for the gang problem and start to come up with a real solution. CDCR’s multi-decade focus on prison gangs had led to gangs taking a more and more central role in prison life, and even life outside of prisons in some neighborhoods. It’s as though by emphasizing how dangerous gangs are, CDCR is making them even more that way. CDCR should recognize that their punitive approach to gangs clearly hasn’t worked, so they need a new approach.

A3N: What does this say about CDCR’s priorities, simply from a public health perspective?

RS: From a public health perspective, the gang issue and the SHU as a response shows how little CDCR cares about the communities that prisoners re-enter after prison.

CDCR runs their prisons with a culture of violence, where misbehavior is punished with a tougher, more restrictive environment and solitary confinement is the ultimate weapon. There is no attempt to use or teach non-violent conflict resolution (which you also see in CDCR’s refusal to negotiate with the hunger-strikers). Training prisoners in non-violence would help deescalate situations in prisons, making conditions safer for guards and inmates, and of course it would do a lot to keep streets safer in the neighborhoods to which people return from prison.

Instead, CDCR reinforces prisoners’ pre-existing tendencies towards violence and “toughness” through their disciplinary strategies, and they often release people straight from the SHU to the streets, which is a virtual guarantee of future failure. Amazingly, it’s the hunger strike leaders who have called for non-violence among prison gangs, while CDCR prefers to act like the toughest gang in the place.

A3N: How do you see this practice of prolonged solitary confinement in California prisons as being part of a broader human rights crisis in the US?

RS: We do have a human rights crisis, because authorities at all levels in the United States refuse to recognize human rights. Let’s not forget that as the California prisoners enter their second month of hunger strike, we have scores of Guantanamo Bay prisoners who have been on hunger strike since the start of the year because of their indefinite detention by our national government.

At the other end, we’ve got local governments like the NYPD doing unconstitutional stop-and-frisks to hundreds of thousands of young men of color, or small-town cops in Texas seizing the possessions of law-abiding passing motorists through abuse of civil forfeiture laws. Reining in the abuse of power through our criminal legal system and law enforcement connects many issues.

A3N: How does solitary relate to the US mass incarceration policies that have resulted in the US now having more total prisoners and a higher incarceration rate than any other country in the world?

RS: With respect to mass incarceration, solitary confinement is like the tip of the iceberg of injustice, except that solitary is less visible than most other parts of the system. Mass incarceration was built around the meme of being “tough on crime,” which plays on fears of violence and disorder as well as racial prejudices.

Fear and racism give license to treat prisoners as less than human, and to subject them to many forms of injustice. This has produced mass incarceration through lengthy sentences for minor crimes and racial bias in the application of drug enforcement powers, among other means. And as the sentences and treatment of small-timers has grown tougher, it has pushed up the toughness on the other end of the scale, where prisons are dealing with those we fear most or hate most.

When you can give 25 years for stealing a pair of socks, then of course you’d invent something much, much worse for people who actually did something wrong, which leads to “tougher” penalties in prison, culminating in solitary confinement, and also the death penalty, which has similar deep racial bias in its application.

A3N: This week you passed the 1,000 signature mark with the Change.org petition started by Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), cited in our introduction above. Can you tell us more about your architectural critique of US prisons and the history of ADPSR’s activism?

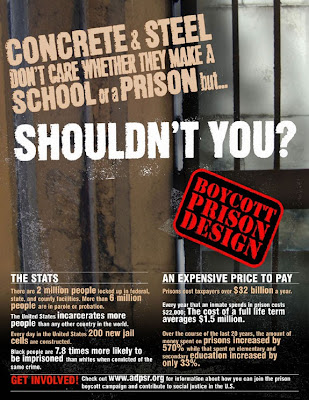

RS: Large-scale prison construction was a necessary component of mass incarceration: in order to hold the over 2.3 million people in prison today. Our country has built close to a thousand new state and federal prisons since the mid-1970’s. Within that system, the construction of specialized supermax prisons was necessary for the large-scale expansion of the use solitary confinement. Since the mid-1980’s, we have built 45 supermax prisons capable of isolating up to 20,000 people, and isolation spaces for 60,000 more people in “segregation” wings or other parts of more conventional prisons.

ADPSR started raising awareness about this issue back in 2004 with a campaign we called the Prison Design Boycott / Prison Alternatives Initiative. The idea back then was that we had so many prisons already that building more would only further the injustices of mass incarceration. We linked prison construction to the lack of investment in community development that was needed to address the root causes of crime in poverty and despair. We encouraged architects to demand public investment in new community centers, health clinics, and affordable housing instead of new prisons and jails.

A3N: Why have you chosen this recent petition as a tactic?

RS: More recently, attention has turned to the use of solitary confinement in US prisons, especially with the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture deciding that healthy adults should never be subjected to more than 15 days of solitary. The average confinement in the U.S. is five years!

ADPSR wanted to follow up on that, since solitary confinement is a policy of spatial control and architecture is such a crucial component of how it works. Supermax prisons in particular contain a number of architectural innovations that allow them to impose isolation, for instance, remotely controlled cell and hallway doors that minimize contact between prisoners and guards.

Because architects’ main professional organization, AIA, has a stated commitment to uphold human rights, we thought that pointing out the contradiction with buildings intended to violate human rights would be a good way to raise awareness about the problem and at the same time make a real contribution to ending the use of solitary confinement.

A3N: In the last few years, the use of solitary confinement in US prisons has come under more public scrutiny, and the profoundly negative effects on prisoners’ mind/body/spirit has been increasingly well-documented. However, much of this badly-needed public discourse presents the torture of solitary confinement as being a ‘mistake,’ ultimately the result of authorities’ ignorance about the negative effects on prisoners’ health. What does the architecture say about the deliberate and pre-meditated nature of this widespread torture in US prisons?

RS: From one perspective, the question is not whether the suffering caused by solitary confinement was pre-meditated or not, as long as one agrees that it is a violation of human rights and should not be done to people. I’ve heard that the designers of California’s Pelican Bay State Prison were told that the policy was that people would be held there for no more than 18 months. In fact, some men have been in there since the day it opened in 1989.

So, there’s a lesson about how much you can trust an executive agency that is granted total power over individuals, granted vast secrecy privileges, has no outside review, and is licensed to use violence. Realizing that the 18 month limit wasn’t trustworthy is just one minor way in which prison authorities and other unsupervised forms of executive power have been found to be abused. Look at the recent NSA spying scandal: their director lied directly to Congress about spying on Americans, and they are so secret that even their budget is classified!

Another way to look at it is to recognize that (along with the death penalty) solitary confinement is the end-point of a culture of violence. Many people like to believe that violence is only a problem when it’s done by people who are labeled as criminals, and that those individuals have the sole responsibility for bad deeds. But it’s more complicated than that. As we discussed earlier regarding CDCR, when our government demonstrates that it leads through violence, that gives a license for everyone else to follow suit. Furthermore, US culture licenses violence in far too many ways: in international affairs (e.g. the invasion of Iraq), with our military-industrial complex, with “stand your ground” laws, in mass media, and through NRA membership, to name a few.

Whether or not solitary confinement is a premeditated form of violence, it’s not an ‘accidental’ part of the culture of violence. Indeed, people who are involved do not even recognize how troubling it is because they are so accustomed to our government doling out punishment and violence.

The flip side of this deep connection is that by drawing the most extreme form of violent punishment into the open and challenging its legitimacy, it creates an opportunity for people to see the bigger picture and challenge the much larger culture of violence in many other ways as well.

A3N: Taking a step back from prisons and solitary confinement units themselves, how has the architecture of the police state manifested in US society outside of prison walls? Are these manifestations more subtle or more overt outside the walls?

RS: One central tool in prison design is the use of surveillance. The most famous prison design in history, Jeremy Betham’s “Panopticon,” was intended to subject prisoners in solitary cells to perpetual surveillance until their psychology internalized the idea of always being watched, at which point they could be returned safely to society. Though the 19th Century prisons he inspired never worked as he imagined, designs of the past few decades have included more and more surveillance, finally approaching this ideal. But this is less rehabilitative than Bentham had hoped: having a direct line of sight into every corner of a prison enables guards to shoot a rifle into every spot in which prisoners might ‘riot,’ or rebel against control.

Surveillance and security-based design are now more prevalent than ever outside of prisons, with the vast multiplication of security cameras, gated communities, and access control at building entries, among other technologies. This system is more subtle than in prisons, and it is often corporate rather than governmental, but it also tends to eliminate truly public spaces where dissent can be organized. ADPSR published the book, Beyond Zucotti Park: Freedom of Assembly and the Occupation of Public Space, to draw attention to this problem, which threatens the basic fabric of our democracy.

More specifically, you see the architecture of fear in the design of schools, where the threat posed by unruly children is now conceived of as a security and policing problem, rather than a need to reinforce positive disciplinary mechanisms in the school administration and at home. Schools are littered with metal detectors and school buildings are increasingly “hardened” to resist potential assaults, which is a built in counterpart to the “zero-tolerance” policies that have been revealed to be ways for kicking poor students of color out of opportunity and into the school-to-prison pipeline. Not that I blame school architects, who are only trying to help, but the role of fear is such that we fail to see the real problem: persistent disinvestment in poor communities of color, a lack of alternatives to the drug business for economic development, and a lack of public infrastructure to support healthy community life, especially for youths.

The same dynamics play out with our public buildings both at home (e.g. courthouses) and abroad (especially embassies), where security guidelines are now deeply entrenched in the design process. While to some degree security measures can be camouflaged with the use of blast-resistant glass and creative landscape architecture, hardening our buildings not only drives up the cost of public construction but more importantly begs the question of whether it is a reasonable response to threatening times. With embassy design, there is a clear connection between the inequities and hostility generated by U.S. foreign policy and an increased need to protect our public face abroad from violent assaults (people grow to hate the U.S. because of our foreign policy). It might be a better plan to have a foreign policy based on human rights and nonviolent conflict resolution than to continually harden our embassies while selling increasingly powerful weapons in unstable regions around the world and privileging ‘US interests’ over the well-being of everyday people in other countries.

At home, having a government that is afraid of its own population (since most of this dates back to Timothy McVeigh’s attack on the Oklahoma City federal building) and our visitors (post-9/11) is not a ‘sustainable’ situation for citizen self-governance. Certainly public employees need safe workplaces, but even if we truly live in more dangerous times than in the past (and I doubt that’s the case), that just calls for more strategies of peacemaking and healing. That can’t happen when every person is viewed as a potential threat and an architecture of inclusion is precluded by security requirements.

A3N: As ADPSR’s petition to the AIA now works towards another 1,000 signatures, what is planned for the future? How else can our readers support your work?

RS: The signature campaign is very important to show AIA that the public really wants to see leadership from the architectural profession on human rights. It’s rare for the public to ask anything of AIA, so more signatures will really get their attention.

That said, myself and others at ADPSR are working hard to broaden this debate and make more people aware of it. We are speaking at AIA events and to AIA local chapters across the country, asking them to write to our national board of directors in support of amending the code of ethics as we propose to do.

We are getting ready to launch a second petition for architecture professors. As a group, they are charged with teaching new architects about professional ethics and having a stronger role for human rights in our ethics code would help inspire their students. We are also soliciting endorsements from associated organizations who have a stake in the issue, from groups that provide design services to indigent populations (e.g. Design Corps), to those who care about solitary confinement specifically (e.g. National Religious Campaign Against Torture).

Lastly, along with folks adding their name to the signature campaign, joining ADPSR is a great way for folks to support our work.

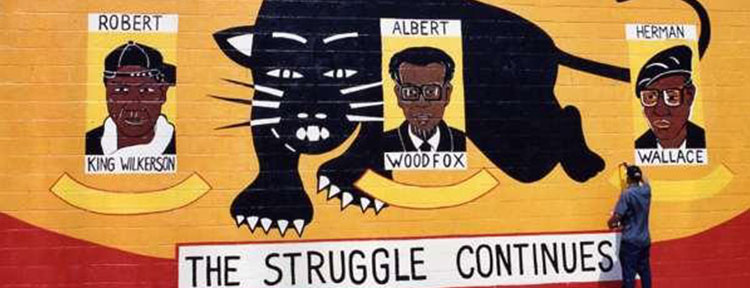

–Angola 3 News is a project of the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3. Our website is www.angola3news.com where we provide the latest news about the Angola 3. We are also creating our own media projects, which spotlight the issues central to the story of the Angola 3, like racism, repression, prisons, human rights, solitary confinement as torture, and more.