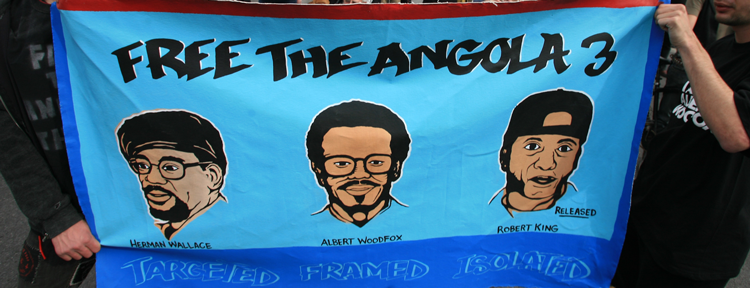

The Angola 3 Case What you need to know

44 years ago, deep in rural Louisiana, three young black men were silenced for trying to expose continued segregation, systematic corruption, and horrific abuse in the biggest prison in the US, an 18,000 acre former slave plantation called Angola.

Peaceful, non-violent protest in the form of hunger and work strikes organized by inmates caught the attention of Louisiana’s elected leaders and local media in the early 1970s. They soon called for investigations into a host of unconstitutional and extraordinarily inhumane practices commonplace in what was then the “bloodiest prison in the South.” Eager to put an end to outside scrutiny, prison officials began punishing inmates they saw as troublemakers.

At the height of this unprecedented institutional chaos, Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace, and Robert King were charged with murders they did not commit and thrown into 6x9 foot solitary cells, where they remained for decades.

Their struggle for justice continued until Robert was released in 2001, Herman in 2013, and Albert in 2016.

Despite a number of reforms achieved in the mid-70s, many officials repeatedly ignored both evidence of misconduct, and of innocence.

The State’s case was riddled with inconsistencies, obfuscations, and missteps. A bloody print at the murder scene did not match Albert, Herman, or anyone charged with the crime and was never compared with the limited number of other prisoners who had access to the dormitory on the day of the murder.

Potentially exculpatory DNA evidence was “lost” by prison officials—including fingernail scrapings from the victim and barely visible “specks” of blood on clothing alleged to have been worn by Albert.

Both Albert and Herman had multiple alibi witnesses with nothing to gain who testified they were far away from the scene when the murder occurred.

In contrast, several State witnesses lied under oath about rewards for their testimony. The prosecution’s star witness Hezekiah Brown told the jury: “Nobody promised me nothing.” But new evidence showed Hezekiah, a convicted serial rapist serving life, agreed to testify only in exchange for a pardon, a weekly carton of cigarettes, TV, birthday cakes, and other luxuries.

“Hezekiah was one you could put words in his mouth,” the Warden reminisced chillingly in an interview about the case years later.

Even the widow of the victim after reviewing the evidence believed Herman and Albert’s trials were unfair, expressed grave doubts about their guilt, and called upon officials to find the real killer.

Herman’s conviction was finally overturned in October 2013. Although his trial was riddled with evidence of prosecutorial misconduct and other constitutional violations, it was the systematic exclusion of women from his jury in violation of the 14th Amendment that freed him. Tragically he died 3 days later from liver cancer. For Herman, justice delayed was justice denied.

Albert’s conviction was overturned three times by judges citing racial discrimination, prosecutorial misconduct, inadequate defense, and suppression of exculpatory evidence. While the case worked its way through endless appeals, Louisiana officials refused to release Albert from solitary, even when no longer convicted of the crime, because “there’s been no rehabilitation” from “practicing Black Pantherism.”4

In June 2015, a Federal Judge courageously ordered Albert's immediate release and barred a retrial stressing the “Court's lack of confidence in the State to provide a fair third trial." This extraordinary remedy was also frozen pending yet another series of appeals.

Finally, Albert was released in February of 2016, 43 years and 10 months after first being put in isolation for a crime he didn’t commit.

In 2000, Herman, Albert and Robert filed a civil lawsuit challenging the inhumane and increasingly pervasive practice of long-term solitary confinement. Magistrate Judge Dalby described their decades of isolation as “so far beyond the pale” she could not find “anything even remotely comparable in the annals of American jurisprudence.” Over the course of 16 years, this seminal case detailed unconstitutionally cruel and unusual treatment and systematic due process violations at the hands of Louisiana officials and inspired worldwide action to end long term solitary.

We believe that only by openly examining the failures and inequities of the criminal justice system in America can we restore integrity to that system.

We must not wait.

We can make a difference.

As the A3 did years before, now is the time to challenge injustice and demand that the innocent and wrongfully incarcerated be freed.