Plantations Were Prisons: Mobilizing for the Aug. 19 Millions for Prisoners Human Rights March in Washington DC

–Part one of an interview with Law Professor Angela A. Allen-Bell

By Angola 3 News

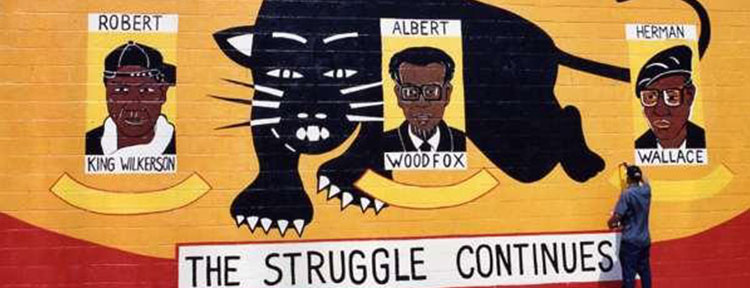

Robert H. King and Albert Woodfox of the Angola 3 are issuing a call to everybody concerned about the human rights of US prisoners: “We know the economic situation for African Americans, other minority communities, and poor whites is very difficult. However, if there is any way possible for you to get to the Millions for Prisoners Human Rights March in Washington DC on August 19, so that your voice can be heard, so that we can speak in one voice, please join us. Enough is Enough!”

Albert Woodfox was released from prison in February, 2016 after over 43 years in solitary confinement. Robert King, the other surviving member of the Angola 3, spent 29 years in solitary confinement until his release in 2001. Along with personally traveling to Washington DC for the March on August 19, both King and Woodfox are currently working to spread the word and raise awareness about the upcoming event.

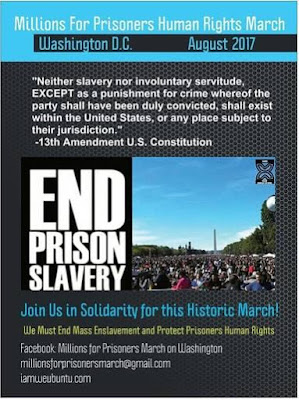

The August 19 March will gather near the White House, in Lafayette Park, at 12:00 Noon. The organizers “seek to unite activists, advocates, prisoners, ex-prisoners, their family and friends, as well as all others committed to the fight to drastically reduce or eliminate prisons and the prison system, and replace them with more humane and effective systems. Our aim is to expose the prison industrial complex for what it is. We want to challenge the idea that caging and controlling people keeps communities safe.”

Albert Woodfox emphasizes the importance of the March: “This is an opportunity to bring to light a lot of stuff that has been kept in the dark about prisons and the judicial system. August 19 will give an opportunity for a mother, father or grandparents to speak about the horrors of their loved ones being in prison.”

The impact of the US prison system on families is a central focus of the March, and is an issue Woodfox speaks directly to: “If you consider the degrading and humiliating experiences that family members sometimes have to endure just to visit, in my opinion it has risen to the point now where the judge sends an individual to prison, he is also sentencing the whole family.” Furthermore, “because of economic hardship, particularly with minorities, it js very difficult for a family to give the kind of support that they want to give to their loved ones. Those are the kinds of things people will get a chance to talk about on August 19.”

The event’s two core demands involve the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution, which was ratified in 1865, following the end of the Civil War. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, except for prisoners, stating specifically: “Neither slavery, nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

The organizers of the March are demanding that “the 13th amendment enslavement clause of the United States Constitution be amended to abolish legalized slavery in America.” Furthermore, they demand “a Congressional hearing on the 13th Amendment enslavement clause being recognized as in violation of international law, the general principles of human rights and its direct links to” several different issues, including “private entities exploiting prison labor,” “companies overcharging prisoners for goods and services,” and “producing the world’s largest prison population.”

For many years now, the Angola 3 have criticized the existence of legalized slavery in US prisons, particularly given that Angola State Prison in Louisiana (where the Angola 3 organized a prison chapter of the Black Panther Party in the early 1970’s) was built on a former slave plantation, and in its current state is arguably a modern day slave plantation. Robert King extends this critique to today, asserting that: “Because of the 13th Amendment’s impact, there needs to be a reconciliation period. The system is oppressive with economic discrimination, racism, bigotry, and more. We want to make the connections, to show how broad the impact of the 13th Amendment is, and how well thought out it was. It may have been a small idea in 1865 but it has since magnified itself greatly.”

Albert Woodfox argues that the enslavement clause was added to the 13th Amendment “to appease Southern politicians and wealthy men. A lot of people think that slavery is over, but it is not.” Woodfox continues: “Anyone who has been convicted of a felony in this country becomes a slave of the state, and you lose your human rights and in most cases your citizen rights for a long time, in some cases forever. Some states have laws where if you are convicted of a felony, then you lose your right to vote. The American Revolution was about exactly that: ‘taxation without representation.’ If I am a former prisoner and I am lucky enough to get a job, I will be paying taxes but I don’t have the right to vote because I went to prison. Okay, I went to prison and I paid my dues, so why when I come back into society do I not have the basic human right in an organized society and that is to vote. Those are the kinds of things we are trying to bring to light to American citizens.”

As the August 19 March approaches, we are publishing a new interview with Southern University Law Professor Angela A. Allen-Bell. In our discussion featured below, Prof. Bell provides an in depth analysis and further historical context for properly understanding what she argues are the legitimate criticisms presented by organizers and participants in the March.

For example, Prof. Bell confronts the history and legacy of slavery head-on, asserting: “When it comes to African Americans, we have been incarcerated from the time we arrived in this country. Plantations were prisons. The change from incarceration on a plantation, to incarceration in custodial institutions, to incarceration where there are no physical limitations, but where one exists in a state of civic and political oppression, in my view, is nothing more than semantics. Mass incarceration started when slavery started.”

Part two of our interview will be published next week, in advance of the August 19 March.

(PHOTO: Professor Angela A. Allen-Bell)

Can you please explain what your critique of this policy is, and how it relates to your broader critique of institutionalized white supremacy in the US criminal justice system?

Angela A. Allen-Bell: In felony cases that are not death penalty cases, Louisiana seats twelve jurors, but allows a conviction upon the vote of only ten of those jurors.

In 1803, when Louisiana became a territory, unanimous verdicts were required. Non-unanimous verdicts were introduced in Louisiana after slavery ended. This Jim Crow era law made its way to the Constitution of 1898 after a convention of all white males expressed that their: “mission was…to establish the supremacy of the white race.”

The change from unanimity was to: (1) obtain quick convictions that would facilitate the use of free prisoner labor (vis-à-vis Louisiana’s convict leasing system) as a replacement for the recent loss of free slave labor; and (2) ensure African American jurors would not use their voting power to block convictions of other African Americans. In my view, this law:

• Creates an arbitrary system whereby defendants of 48 states are afforded greater 6th Amendment protections than defendants in Louisiana and Oregon, the only two states that allow the use of criminal, non-unanimous juries.

• Establishes an illogical disparity in 6th Amendment protections between state courts and federal courts since all federal courts require unanimous juries (even federal courts in Louisiana and Oregon).

• Contributes to wrongful convictions.

• Ignores the credible research on group thinking, which suggests that unanimous verdicts are more reliable, more careful and more thorough.

• Creates a legal means for prosecutors to discriminate when it comes to jury practices by allowing them to circumvent the US Supreme Court’s 1986 Batson v. Kentucky decision, which prohibits prosecutors from using race as a reason not to select someone for jury service.

• Contributes to the creation of an automated justice system whose aim is speed as opposed to justice and genuine concern for public safety.

• Ignores longstanding 6th Amendment tenants calling for unanimity dating back to the enactment of the 6th Amendment and the time of the Framers.

• Allows different standards between the states and the federal government for the protection of fundamental rights in defiance of the Bill of Rights, which mandates otherwise.

• Undermines public trust in the judicial system.

• Contributes to the oppression of classes of people.

• Contributes to mass incarceration.

We often think of slavery in racial terms. The scale of slavery is often overlooked. When slavery was abolished, it was the largest financial asset in the American economy. This is significant because it speaks to the coveted nature of the system and hints to the veraciousness of the appetite that would have existed to maintain it.

Laws such as the 13th Amendment and Louisiana’s non-unanimous jury law create the appearance of legitimacy in government while simultaneously serving as legal blueprints for the oppression of certain people. They were written to ensure that African Americans could not achieve social or political equality. These laws represent the legislation of oppression and white supremacy. Justice and oppression can’t coexist. Therein lies the problem.

The historical record is replete with examples of this taking form under the cover of law, policy and/or practice. For example, following the end of segregation in Louisiana, the legislature created a Segregation Committee and an Association of Citizens Councils. These bodies were to work in close cooperation with the legislature to preserve white supremacy. One of the things they did was set up programs for parish voting registrars where registrars were trained on how to promote white political control.

Mississippi’s legislature created a Sovereignty Commission for using legislation to maintain white supremacy. Alabama added language to its constitution that prevented people from voting if they were convicted of certain enumerated crimes. The crimes that they included in the legislation came from conviction statistics. They used those statistics to select crimes that African Americans were mostly convicted of and then those crimes were put into the constitutional enumeration with the intent of disenfranchising African Americans.

I encourage people to stop viewing these injustices as solitary wrongs. They are so much more than bad laws or bad policies. Justice seekers must view these laws within the context of the system they were designed in. Fixing these laws will accomplish a very narrow goal: one bad law gone. I discourage a fix. I encourage a solution.

The real issue is the system that plays host to such injustices and human rights abuses. The focus of this generation has to be on systemic change. This is the only way to finally confront the complex layers of institutionalized racism and supremacy in the criminal justice system.

Since the late 1980s, Congressman John Conyers has repeatedly introduced H.R. 40, which calls for the establishment of a “Commission to Study the Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act.” What’s important about this legislation is the aspect that would create a federal commission to review the institution of slavery, the resulting racial and economic discrimination against African Americans, and the impact of these forces on African Americans who are living today. Studies are routinely done in this country concerning lesser matters. It makes logical sense for the government to devote its resources to fully acknowledging the far-reaching impact that slavery has had on us―all of us.

Since slavery ended, there have been too many instances of law and policy being used as an agent of repression. And it is law and policy that has defined our economic, political and social existence. At what point have we collectively confronted this reality and what it has done to the infrastructure of our government and our legal system? The upcoming march wisely seeks to confront this void.

A3N: What is the current status of the non-unanimous jury rule in Louisiana? Are there currently any challenges to it in the courts or elsewhere?

AB: The law remains in the criminal code and in the state constitution. It continues to be championed and used by many prosecutors on a regular basis. At the same time, there are continuous defense challenges in Louisiana (and Oregon) state courts. Louisiana courts render predictable and ritualistic rulings that maintain the status quo.

On rare occasions when Louisiana courts have agreed to review the merits of non-unanimous jury challenges, they harmoniously declare that the solution to this injustice is to place a toilsome burden of proof on criminal defendants. Notably, on February 9, 2017, in the case of State v. Lee, Orleans Parish Criminal District Court Judge Arthur Hunter ruled that proof of disproportionate impact requires the testimony of a statistician or social scientist who has:

“[P]reformed a peer-reviewed study which looked at raw data concerning jury verdicts. This data would have been divided based on unanimous and non-unanimous juries. The data then would have been analyzed for guilty, not guilty, hung juries, and overturned verdicts. The data would also be teased apart based on race, gender, and even religion…To show disparate impact, the court needs to see a full-scale study which looks at the numbers to provide conclusive demographic data…”

There are ongoing efforts by Oregon and Louisiana defense attorneys to have this issue reviewed by the US Supreme Court (who last spoke on this issue in its flawed, 1972 Apodaca v. Oregon plurality opinion). A mounting grassroots advocacy effort led by the ACLU of Louisiana, the Innocence Project New Orleans, myself and a few other local lawyers and exonerees devoted to the dismantling of this law has also formed.

A3N: In your Mercer Law Review article and earlier in this interview, you present the historical context for the non-unanimous jury rule by citing how the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, except for prisoners. The 13th Amendment is a central focus of the upcoming Millions for Prisoners Human Rights March in Washington DC August 19.

In your opinion, in order to understand our present circumstances, how significant are these historical origins of the US prison system? What is the legacy of the laws criminalizing former slaves, known as the Black Codes and the convict lease system that accompanied the 13th Amendment’s legalization of slavery for prisoners?

AB: After Abraham Lincoln was elected, Southern states started to secede from the Union. The Civil War ended in May 1865. The 13th Amendment was ratified in December 1865. The 13th Amendment was an attempt by Congress to get those Southern states back. Thus, the exceptions clause. The primary architect of the legislation was a slaveholder. In his recent book, Slaves of the State, Dennis Childspoignantly describes this legislative charade. He writes:

“The grandest emancipatory gesture in U.S. history contained a rhetorical trapdoor, a loophole of state repression, allowing for the continued cohabitation of liberal bourgeois law and racial capitalist terror; the interested invasion of ‘objective,’ ‘color-blind,’ and ‘duly’ processed legality by summary justice and white supremacist custom; and the constitutional sanctioning of state-borne prison-industrial genocide.”

The legacy is that they all contributed to the continuation of the conditions of slavery. They collectively ensured that slavery never ended, but merely changed forms. These historical origins help us understand the current state of affairs as much as they underscore the significance of the upcoming march, which seeks to eradicate these structural defects in our “injustice” system.

A3N: You write that your Mercer Law Review article “advocates against impersonal, mechanized systems of justice that are built upon defendants, dockets, cases, quotas, formulas and rapidity. This article calls for the justice community to see cases in a highly personal way—to see cases as stories written about humans.”

In this same vein, even human rights activists can perhaps get so caught up in the statistics of injustice (like mass incarceration and the racially discriminatory so-called “war on drugs.”) that we can downplay or even forget the human story behind the statistics. What is that story? What do you think is the US prison system’s impact on prisoners, prisoners’ families, and the broader human community?

AB: Nothing about who we are as a mass incarcerator should be viewed as a current event. When it comes to African Americans, we have been incarcerated from the time we arrived in this country. Plantations were prisons. The change from incarceration on a plantation, to incarceration in custodial institutions, to incarceration where there are no physical limitations, but where one exists in a state of civic and political oppression, in my view, is nothing more than semantics. Mass incarceration started when slavery started. And, since that time, African Americans have experienced some form of imprisonment―the differences are in the degrees.

The notion of incarcerating people as a form of individual punishment did not always exist. The practice was to convict then punish, not to confine. Death and corporal punishment were used extensively before opposition to the death penalty formed. The practice of using physical structures to separate people from society came as an alternative to this.

These institutions (along with immigrant detention centers) have transcended the Southern racist and exploitative agenda and morphed into incubators for capitalist contrivances. At this moment in America, there are over 2.2 million incarcerated people. Incarceration has increased by more than 500% in the last forty years. My research does not offer justification for such sweeping efforts to lock people up. What it does show is that laws, policies, racism, bias, unjust practices, abuses and a nearly automated judicial system has led to the creation of what I liken to an organized human trafficking system where poor people are ushered through courts on virtual conveyor belts and funneled into the unyielding grip of custodial detention and state supervision.

As people understand this, they will approach conversations about prisons and convictions with caution and begin to develop the capacity to see inmates as something more than just “defendants” or “criminals.” This matters because perception and characterization shapes our level of empathy.

In no way am I suggesting that every prisoner is free of culpability and is undeservingly in custody. I don’t feel that way at all. I am suggesting that the system is so inherently flawed and so riddled with bias (both implicit and explicit) that it often treats the innocent and the guilty the same and, once in it, the system engulfs a person and often fast-tracks them to becoming their worse self.

Prisons are breeding grounds for sickness, recidivism, exploitation, cruelty and destruction. In their current form, they are not a good use of public dollars. With this appreciation, we can no longer dismiss conversations about prisoners. We can’t rest on the notion that inmates put themselves there.

In this same vein, we must fight the overuse and abuse of solitary confinement, both in the general population and on death row. This system affords too much unchecked authority to prison officials. The harms far outweigh the benefits. The situation has been too well studied to be refuted at this point. Prolonged solitary confinement causes anxiety, depression, anger, cognitive disturbances, perceptual distortions, obsessive thoughts, paranoia, psychosis and a host of other medical and emotional challenges. It costs more. It is disproportionately used on minorities and vulnerable populations, such as the mentally ill and members of the LGBT community.

This march represents a moment for people to see what prisons are as much as what they are not. Certainly, they are needed for public safety in some instances. But the scale of the situation in the United States far exceeds what is necessary for public safety.

Prisons create and ensure an underclass. Prisons provide a free labor base. Prisons destroy families and kill potential in people. Prisons provide profits to those who have a stake in them.

–Angola 3 News is a project of the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3. Our website is www.angola3news.com, where we provide the latest news about the Angola 3. Additionally we are also creating our own media projects, which spotlight the issues central to the story of the Angola 3, like racism, repression, prisons, human rights, solitary confinement as torture, and more.