Never Silenced, Herman Wallace’s Spirit is Smiling –An interview with filmmaker Angad Singh Bhalla

Never Silenced, Herman Wallace’s Spirit is Smiling

–An interview with filmmaker Angad Singh Bhalla

By Angola 3 News

Canadian filmmaker Angad Singh Bhalla has never shied away from examining politically controversial topics. Nor does he play down his own artistic goal of using media to foster political change. Bhalla’s first independent work, entitled U.A.I.L. Go Back amplified the voices of Indian villagers resisting an alumina project backed by the Canadian company Alcan. The film became an important organizing tool used to pressure Alcan into ending its involvement in the project.

Bhalla has since co-founded Time of Day Media.and while working as a community organizer for immigrant rights, he produced videos for the Service Employees International Union, Working America, the Center for Constitutional Rights and other groups. His award-winning short on the lives of Indian street artists, Writings on the Wall, was broadcast on Canada’s Bravo! and Al Jazeera English.

Bhalla’s debut feature documentary was the 2012 film Herman’s House, about Herman Wallace of the Angola 3 and the collaborative project Wallace worked on with artist Jackie Sumell, entitled The House That Herman Built. The film screened at more than 40 festivals, was distributed theatrically in the US and Canada, and won an Emmy Award for its 2013 POV broadcast on PBS.

The newly released, interactive website-based documentary film made by Bhalla, entitled The Deeper They Bury Me: A Call from Herman Wallace, builds upon Herman’s House by further examining Herman Wallace’s life, following Wallace’s death from liver cancer on October 4, 2013, just three days after being released from prison. This latest film has already been well received. Along with a recent screening at the 28th annual International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, The Deeper They Bury Me has also been selected by Favourite Website Awards as the “Site of the Day” for December 14, where it is being displayed on the website’s front page for the full day.

In this interview, filmmaker Angad Singh Bhalla discusses his latest film, The Deeper They Bury Me, while also reflecting upon his 2012 film Herman’s House, his personal relationship with Wallace and more. Bhalla concludes the interview with a focus on the call by Amnesty International and the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3 for the immediate release of Albert Woodfox, who is the last of the Angola 3 behind bars. Despite three overturned convictions, Woodfox remains in prison and in solitary confinement, where he was first placed over 43 years ago.

(VIDEO: Coverage of the panel discussion following a recent screening of The Deeper They Bury Me at the 53rd New York Film Festival. Photos from this event by Lindsey Seide/NFB are featured below alongside still images taken from the film itself.)

Angola 3 News: Can you please tell us how you first heard of Herman Wallace and the Angola 3?

Angad Singh Bhalla: I first heard about Herman Wallace and the Angola 3 in 2002, shortly after Robert King’s release from prison. Artist Jackie Sumell organized a lecture for King at Stanford University, where I co-hosted a political talk show on the campus radio station at the time. Robert King remains one of the most memorable discussions we ever had on that show.

(PHOTO: Filmmaker Angad Singh Bhalla at NY Film Festival)

A3N: Your bio states that you use your films “to call attention to voices we rarely hear” and “as a means of fostering political change.” Your 2012 film Herman’s House certainly helped to amplify Herman’s voice and it created more public attention to Herman and the Angola 3.

Looking beyond the immediate campaign for Herman’s release from prison and solitary confinement, as well as the continuing call today for Albert Woodfox’s release from prison and solitary, what do you feel were the central messages that you sought to focus on with Herman’s House?

ASB: With the documentary Herman’s House, the real central message was that Herman Wallace, like all the other people we incarcerate, is a human being. As simple as that sounds, I think the prison industrial complex’s most devastating impact has been to dehumanize the people it incarcerates. We did not show any images of prisons in the documentary because I believe even the very sight of a prison can contribute to this dehumanization process.

With the film I hoped to transform Herman and indirectly everyone else we incarcerate from a convict or felon into a brother, a mentor, a friend and like all of us a dreamer. In that sense, unlike other profiles, I was not as focused on Herman’s innocence. While Herman was wrongfully convicted, I wanted to focus on the nature of his incarceration which ties him to the 2.3 million other Americans we put in prison.

A3N: Now with the release of The Deeper They Bury Me a few years after Herman’s House, do the fundamental themes and issues addressed in this film differ at all? Otherwise, how do you think The Deeper They Bury Me complements Herman’s House?

ASB: Similar to Herman’s House, I think the theme of humanizing Herman and focusing on the conditions of his incarceration remain in The Deeper They Bury Me. But at the same time I think The Deeper They Bury allowed me to bring more attention to the specific circumstances around Herman’s story.

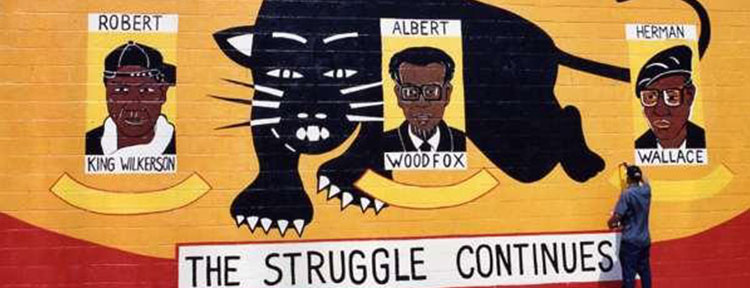

In that sense I tried to highlight Herman’s past growing up in a segregated New Orleans to highlight how America’s racist history relates directly to America’s racist present. This experience of it being more a telling of Herman’s story by Herman, allowed me to explore his political convictions and work with the Black Panther Party more than I could in the film. I tried to highlight Herman’s position as a political prisoner in The Deeper They Bury Me.

Overall I think the interactive aspect compliments the film by providing much more of the historical and political conditions of Herman’s incarceration. While Herman’s situation may have been unique, those conditions are not. I hope that through this interactive telling of Herman’s experience viewers begin to understand that history is present.

There is a reason that in the United States, people of color account for nearly 60% of the imprisoned while making up only 30% of the population. There is a reason that the United States, black Americans are six times more likely to be imprisoned than white Americans.

These reasons are not simple and go back to the founding myths of this country, which is why there are more black men under some form correctional supervision (imprisoned, on parole, or probation) than were enslaved in 1850.

A3N: The interactive format of The Deeper They Bury Me is very cutting edge. Can you tell us more about the various interactive features that our readers will find when they go to watch the film? What do you feel that this interactive format adds? How does it change or enrich the viewing experience?

ASB: Well, the entire experience is set up to determine what aspects of Herman’s life the user wants to hear him talk about. In many ways the prison industrial complex relies on framing spaces as tools of punishment and coercion. This interactive format allows people to actually explore 3D replicas of Herman’s cell, his dream bedroom, and prison dorm. Interacting with these spaces in relation to one another, I think, allows users to really question our notions of freedom and confinement.

While not all the environments are available at the same time, the user gets to decide which spaces she wants to linger in and which elements of Herman’s story she wants hear more about. Not being constrained by a linear narrative structure and the idea of always moving an audience forward, the interactive format provides audiences the opportunity to go deeper into what would be considered Herman’s back-story in a traditional documentary.

While of course the linear documentary is my point of reference in many ways, The Deeper They Bury Me is an entirely different kind of storytelling. It will never replace the linear form, but at the same time, it allows the user to get to enter Herman’s world from the point that is most relevant to them. Further, as a tool, being able to access each of the 25 one-minute videos independently allows activists to craft a narrative that best suits their campaign work. Herman’s story is so relevant for today’s young activists that I wanted to try to tell it in a form that is more relevant to young people who communicate so much now online.

(PHOTO: Harry Belafonte at NY Film Festival screening)

A3N: Along with your two films about Herman, in 2014 another Angola 3-related film was made in Canada, entitled Hard Time, by Ron Harpelle, which focused on Robert H King. Seen in the context of these three films, how do you think Canadian audiences have responded to the story of the Angola 3?

ASB: I think like most audiences, Canadian audiences are shocked when they first hear the story of the Angola 3. I think the Angola 3 story may find more receptive outlets in Canada and other countries outside the US simply because people feel good pointing out injustices happening in other countries.

In the ‘learn more’ section of site we included the fact that Aboriginal Canadians are ten times more likely to be incarcerated that other Canadians. As much as we Canadians might like to deny it, our criminal justice system extends from a sordid history of oppression and remains a racist tool of social control.

(PHOTO: NY Film Festival speaker panel)

A3N: What is the significance of the National Film Board of Canada’s (NFB) involvement with The Deeper They Bury Me, both producing it and hosting the film on their website? How did the NFB become involved with the film?

ASB: In 2010, I approached the NFB looking for their support to help produce Herman’s House, the linear film. It was producer Anita Lee at the NFB, who proposed the idea of creating an independent interactive piece that became The Deeper They Bury Me.

The NFB has been leading the development of interactive online storytelling since the field first emerged, so I was extremely excited that they saw interactive potential in Herman’s story. The NFB is not only a Canadian institution but it has a global legacy of producing critical independent documentary films, including films that inspired me to get into the field, like Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and The Media. As an NFB production, The Deeper They Bury Me becomes a part of an essential collection and will most importantly introduce Herman’s Story to an even broader audience.

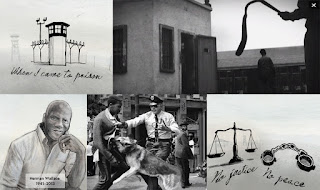

A3N: In October, 2013 after battling liver cancer for several months, Herman Wallace was released from prison. Just a few days later, he passed away in the company of family and friends. In the days following, tributes to Herman ranged from US Congressmen to the Washington Post and New York Times. As someone who has studied Herman’s life so closely, can you please reflect on his life and share with us what you think his legacy is today?

ASB: It’s would be hard to overstate the impact Herman has had on my life. More than merely the subject of my past two documentary projects, over the 6 years that we conversed by phone he became both a friend and teacher in so many ways.

To be exonerated and released three days before passing away was undoubtedly tragic, but in so many ways Herman’s story is one of victory. His legacy will forever be that of someone who stood up to injustice and won. Not in the Hollywood way of winning where everything turns out okay in the end but in the messy way people who have struggled for justice get to win.

For four decades the system tried to silence Herman for his resistance. But like Herman’s poem from which this piece is titled, the deeper they tried to bury Herman the louder his voice became. The system had planned for Herman to die in prison, and even through he enjoyed only three days of freedom, he defied that system and that defiance made headlines around the world.

Herman decided long ago that he was willing to sacrifice his life to serve as symbol for so much of what is wrong with America’s prison industrial complex. As sad as I am that I lost a friend, I can feel his spirit smiling with the knowledge that his struggle and eventual victory is still inspiring a new generation of activists.

A3N: We in the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3 have sought to honor Herman’s legacy by “turning grief into strength,” and working for the immediate release of Albert Woodfox from both prison and solitary confinement, so that he will be able spend more time outside prison walls than Herman was able to. In February 2013, several months before Herman’s cancer diagnosis, Albert’s conviction was overturned for a third time. Subsequently, in November 2014, this third overturned conviction was upheld by the US Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and then in June 2015, US District Court Judge James Brady ruled for Albert’s immediate and unconditional release, as well as banning a retrial. Yet, to this day Albert remains in solitary confinement.

What do you think about Albert’s treatment in recent years, especially following Herman’s death? How about this US “criminal justice” system where an elder prisoner’s conviction can be overturned for a third time, but still be held captive and in solitary confinement?

ASB: Sadly nothing about Albert’s treatment both prior to and following Herman’s death surprises me.

Like Herman, Albert has always been used by the state as an example to others who might fight back against state oppression. There is not a criminal justice system in America, there is a system of social control that relies on incarceration and violence. The state must put all the resources it has at its disposal to keep torturing people like Albert to make sure other people who even consider exposing the system’s contradictions think twice.

Look at how the NYPD have been continuing to harass and abuse Ramsay Orta, the man who recorded the NYPD murder of Eric Garner and his family. Albert’s case has never been about the evidence that had him convicted of Brent Miller’s murder, because there isn’t any. It has always been about the state displaying its ruthless power.

Unfortunately for the state, the truth is the truth and the more the state tries to display power the more desperate and pathetic it looks.

(PHOTO: Herman Wallace, left, with Albert Woodfox, right)

–Angola 3 News is a project of the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3. Our website is www.angola3news.com, where we provide the latest news about the Angola 3. Additionally we are also creating our own media projects, which spotlight the issues central to the story of the Angola 3, like racism, repression, prisons, human rights, solitary confinement as torture, and more. Our articles and videos have been published by Alternet, Truthout, Counterpunch, Monthly Review, Z Magazine, Indymedia, and many others.