Healing Our Wounds: Restorative Justice Is Needed For Albert Woodfox, The Black Panther Party & The Nation–An Interview With Law Professor Angela A. Allen-Bell

By Angola 3 News

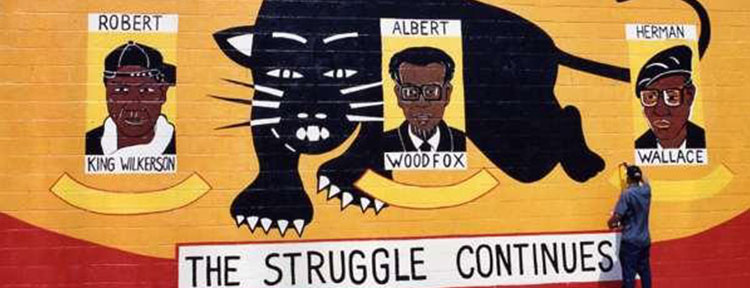

On Monday, June 8, 2015, US District Court Judge James Brady ruled that the Angola 3’s Albert Woodfox be both immediately released and barred from a retrial. The next day, at the request of the Louisiana Attorney General, the US Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a temporary stay of release set to expire on Friday, June 12.

As the week intensified following Judge Brady’s ruling, both Albert Woodfox and his family, friends & supporters wondered if he would finally be released over 43 years after first being placed in solitary confinement. Amnesty International USA launched a petition calling on Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal to honor Judge Brady’s ruling.

On June 9, US Congressman Cedric Richmond (LA-02) issued a statement declaring that “Attorney General Caldwell must respect the ruling of Judge Brady and grant Mr. Woodfox his release immediately…This is an obviously personal vendetta and has been a waste of tax payer dollars for decades. The state is making major cuts in education and healthcare but he has spent millions of dollars on this frivolous endeavor and the price tag is increasing by the day.”

On June 11, eighteen members of the Louisiana House of Representatives voted unsuccessfully to pass a resolution (H.R. 208) urging Attorney General Caldwell to stop standing in the way of justice, withdraw his appeals, and let Judge Brady’s unconditional writ and release ruling stand.

However, on Friday, June 12, the Court responded by scheduling oral arguments for late August and extending the stay of release at least until the time that the Court issues its ruling later in the Fall.

Among those who communicated with Albert during that emotional week was Southern University Law Professor Angela A. Allen-Bell. In the days following Judge Brady’s ruling, she was a featured guest on several television and radio shows that focused on Albert’s case, including National Public Radio. In this interview with Angola 3 News, Prof. Bell discusses her new law journal article and reflects upon the latest developments in Albert’s fight for freedom. She argues that recent Angola 3-related media coverage in the US is becoming “more substantive,” and that this month “the media got bolder and began digging deeper than just a soundbite.”

Literally hundreds of news websites around the world published articles about Judge Brady’s ruling. The New York Times, who in an earlier editorial from 2014 declared Albert’s four decades in solitary to be “barbaric beyond measure,” chose a headline for their June 10 article that cited Albert’s “Torturous Road to Freedom.” The next day, the NY Times reprinted an Associated Press article entitled “What Has Louisiana Got on the Last of the Angola Three?” Answering the question posed by the headline, the articles states: “Woodfox’s long-simmering story has been the subject of documentaries, Peabody Award winning journalism, United Nations human rights reviews and even a theatrical play. It’s a staggering tale of inconsistencies, witness recants, rigged jury pools, out-of-control prison violence, racial prejudice and political intrigue.”

Media coverage in the state of Louisiana itself also seems to be improving. For example, writer Emily Lane of the NOLA Times-Picayune responded to Brady’s ruling with a series of in-depth articles, focusing on the specifics of how and why Albert has been in solitary for over 40 years, as well as the physical and mental impact of such treatment. In another article, the Times-Picayune quoted extensively from a statement made by Teenie Rogers, the widow of slain prison guard Brent Miller. “I think it’s time the state stop acting like there is any evidence that Albert Woodfox killed Brent,” Rogers said. Meanwhile, Albert remains in solitary confinement, with Louisiana authorities “not letting up on” the “last of the ‘Angola3.'”

Our first interview with Prof. Bell, entitled Prolonged Solitary Confinement on Trial, followed the release of her 2012 article written for the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, entitled “Perception Profiling & Prolonged Solitary Confinement Viewed Through the Lens of the Angola 3 Case: When Prison Officials Become Judges, Judges Become Visually Challenged and Justice Becomes Legally Blind.”

This new interview, now our third, is timed with the release of of Prof. Bell’s latest article, published by the University of Miami Race & Social Justice Law Review, entitled “A Prescription for Healing a National Wound: Two Doses of Executive Direct Action Equals a Portion of Justice and a Serving of Redress for America & the Black Panther Party.”

Angola 3 News: How does your new law journal article, A Prescription for Healing a National Wound, relate to and ultimately build upon your previous two articles, Perception Profiling and Activism Unshackled?

Angela A. Allen-Bell: The three articles share a common thread and that is that the Angola 3 case was the inspiration for each of the articles. The Angola 3 case is a fusion of complexities, including race, justice, corrections practices, abuse of power, official misconduct and politics. Each of the three articles explores a different theme in the case.

The 2012 publication, Perception Profiling, explores the constitutional implications of long term solitary confinement.

The 2014 publication, Activism Unshackled, exposes the harsh response of the government to the Black Panther Party (BPP) and declares the BPP to be victims of something akin to domestic terrorism.

The 2015 publication, A Prescription, calls for redress and offers a solution for the nation and the BPP to heal from the traumas experienced during the historical period of the BPP’s existence.

A3N: You write that “Redress is the aim because it is broader than justice. Redress is also the goal because, when delivered, it has the impact of bringing distant human rights aspirational goals to a local and identifiable place in our society.” For folks that have not yet read A Prescription, can you please explain what you mean by “redress?”

AB: When I use the term redress, I simply mean “remedy.” In this section of the paper, I am calling people’s attention to the fact that the pursuit of justice is largely personal. It involves personal vindication.

Contrarily, redress, through a restorative justice model, is much more expansive. Restorative justice not only considers the victim; it also considers the impact on society. It seeks to heal both simultaneously.

We have never healed from many of the racial traumas that afflict this nation. The evidence of this is on display in the media consistently. Unaddressed traumas are the underlying explanation for some police feeling comfortable gunning down African American males in absence of a legitimate threat of bodily force. That psyche developed during the lynching era.

Unaddressed traumas explain educational and discipline policies that fast track poor children and children of color from schools to prison. Long ago, it was decided that certain groups were intellectually inferior and, as such, could best serve as an underclass.

Unaddressed traumas explain the decision to select an African American church as the setting for an act of domestic terrorism, as with the recent massacre in Charleston. That happened so many times during the Civil Rights Era, it almost became sport. We must recognize that patterns continue unless and until a conscious choice is made to stop them. That is why I advocate for redress through a restorative justice approach. It is my attempt to reconstruct the paradigm and pursue a path of healing.

A3N: Why do you feel that redress is an appropriate response to the political repression faced by the BPP and other leftists groups during the era of the FBI’s COINTELPRO and beyond? What are the benefits of redress?

AB: In my opinion, it is the only appropriate response because of the state we presently find ourselves in as a country. We excel at technology. We are masters at warfare. We are an international might. We have accomplished all these things, but we have yet to master the art of loving each other. I am not using the word love in a superficial way. I am using it as a verb. I mean love in a profound way. I mean love that blinds your view of the outside and affixes your eyes on the heart of your brother or sister. This is a terrible indictment on us collectively. This is the legacy that racism, subjugation, oppression and dehumanization left behind.

We need collective healing from a number of social traumas, such as lynchings, racist medical, educational and criminal justice practices, all of the vestiges of slavery, and the neutralization of or attempts at neutralization where civil rights activists and organizers are concerned. These things have caused us not to be well. This article picks one social trauma to address and that involves what was done to the BPP. It serves as a template to addresses the others.

The article discusses several benefits to redress. They include: the timely ability to shape good policy; the achievement of accountability; the furtherance of human rights goals and objectives; and the prevention of history repeating itself. Redress in this instance will help society and the BPP. It will allow us to move pass this chapter onto the next chapter then the work must begin again and again until we have peeled away the many layers to this dysfunction that we are experiencing as a human family.

A3N: You write further that “the goal is to achieve restorative redress—for America in general and the BPP in particular—through executive direct action correcting official history by way of a proclamation and an executive order granting amnesty—with a focus on healing for the nation, victims and perpetrators (as opposed to focusing on the limiting notion of punishing the perpetrator).” Why do you focus on Executive Direct Action as the best means for redress?

AB: Executive direct action is a presidential power that is highly effective because it can accomplish a goal without the paralyzing complication that a bureaucracy involves. It is used more than many people know and was chosen in this instance because of the expediency of the process and the complexities of this historical ordeal. It was also chosen because traditional methods have failed and/or will not work.

In the article, I share detailed reasons why courts, hearings, legislation and executive action on the state level were all eliminated as possible forms of redress.

A3N: Over two years ago, on Feb. 26, 2013, Albert’s conviction was overturned for a third time. However, today, even following last week’s ruling by Judge Brady, Albert remains behind bars and in solitary confinement! Reminiscent of fictional stories by George Orwell or Franz Kafka, how does something like this actually happen? What does it say about the legitimacy of the broader so-called criminal ‘justice’ system in the US?

AB: Like the United States Constitution, our criminal justice system was born in sin and iniquity. Our modern criminal justice system has very little to do with dispensing justice or keeping citizens safe. It was designed as a tool to further a caste system that was started before slavery. It has become a lucrative enterprise for many. Many laws were written with these considerations in mind. This system is now a machine. Add the utter disdain that this country has had for African American men to this assembly line environment and you might be able to rationalize what Albert Woodfox is experiencing.

The justice system has dealt an unjust hand to many people of color and poor people, but it has been particularly harsh when it comes to the BPP. They were arrested regularly and locked up often, but, in most cases, charges were dropped or the BPP member won the case. The criminal justice system was intentionally used as tool to disrupt their political and social activities. That detail has largely been suppressed from the public.

This is not to suggest that we don’t need a justice system or jails. I feel both are needed. My only point is that there is a design defect. When that happens, demolition must follow. In my view, this is where we are in our criminal justice journey.

A3N: Any other thoughts on this month’s events?

AB: Last week, I saw members of the international community intensify their response. That was beautiful and their support has been consistently present and helpful. That is greatly appreciated.

There were several welcomed, new developments at home. One was the more substantive media coverage that took place in the United States. The media got bolder and began digging deeper than just a soundbite. Much of the coverage explored the actual evidence (or lack thereof) in the case and many outlets courageously did a critical analysis of America’s solitary confinement practices.

Most impactful of all is the fact that, last week, Americans reclaimed their power. Grassroots activism and direct citizen participation is the key ingredient in any social change movement. That happened last week. Even more significant, a heightened interest took place in Louisiana, which is a very conservative, “tough on crime” kind of place.

The new development is that Louisiana citizens who, in spirit, support locking folks up have become opposed to the State’s decision to spend well over six million taxpayer dollars on the criminal prosecution and the civil litigation in the Angola 3 case. Many more Louisiana citizens, after realizing this case was built on deals with criminals and false testimony and official misconduct, voiced their opposition to what State officials have done and continue to do in the case.

Others have begun to see that corruption has played a part in this case as contracts for legal work on the Angola 3 case have been awarded to associates who have a financial incentive to engage in dilatory tactics at the expense of Louisiana taxpayers.

Other citizens were called to act because the global reputation of the United States is being compromised as the world looks at us in judgment for this human rights abuse. The next step is to see this channeled and to see mobilization follow.

A3N: While it is important to examine how Albert and the Angola 3’s story represent much broader issues of injustice, we also do not want to forget that above all, Albert is a human being. Shifting to a more personal level, can you tell us about your visits with Albert? What have you learned from Albert?

AB: It is my personal feeling that the Angola 3 were anointed and called to do the courageous and significant work they have done both collectively and individually. It is a message I often speak to them. In my view, this is why they weren’t murdered or harmed behind bars by other inmates.

It is also my feeling that this is the source of grace that Albert displays. He has his vulnerable, grief-stricken moments, but he has many more days of peace. The suits the Angola 3 filed and the organizing they did has led to better conditions for many others.

Albert has taught me: how to speak mightily with a few words; how to be patient while never waiting; that freedom has more to do with liberation than it does location or station; that Christ, who was a carpenter himself, consistently uses the least valued people (in man’s terms)─people who the world could see little value in─to accomplish some of the most profound changes; how to fight evil without ever balling a fist or loading a weapon; how a liberated mind in the head of an African American man often results in a symbolic, social warning label; how to resist the urge to allow fear to serve as an excuse for lack of service; how to manifest the Biblical teaching that love is the greatest commandment of all; and, how to minister without preaching.

A3N: How much physical contact, if any, has been allowed during visits? Based on your experience visiting Albert, how important is it for prisoners to be able to hug and express friendship through human touch with their visitors?

AB: Louisiana officials have branded sixty-eight-year-old Albert Woodfox, who is afflicted with a litany of health problems, the most dangerous man in America, despite their own records documenting that he is and has been a model prisoner.

In fulfillment of this marketing strategy and act of wordplay, Albert’s visits are restricted. They are no contact, limited to an hour and are observed closely. Even the Bible recognizes that man was not born to be alone. Isolation violates biblical principles, as well as medical research, legal precedent and human rights principles.

The practice of prolonged isolation even runs counter to the thinking of Pope Francis, US Supreme Court Justice Kennedy, certain doctors, academics, human rights advocates and architects, Human Rights Rapporteur Juan E. Mendez, the American Bar Association, the American Correctional Association, the National Defense Association and many other credible voices. It especially makes no sense when a person is elderly and harmless as was the case with Herman Wallace and as is the case with Albert Woodfox.

Society is better off when inmates maintain humanity and also when they do not become totally institutionalized. Innocent human touch and meaningful interaction are quintessential ways of preserving humanity.

A3N: Any further reflection on the personal impact of both your research & writing about the Angola 3 as well as your relationship with Albert?

AB: These things have impacted me profoundly. They have made me keenly aware of our social regression in this country. The shift from us being somewhat of an interconnected unit during the 1960s and 1970s to a self-driven population has crippled progress where social gains are concerned. This is not meant as a judgment or an indictment. This is meant partially as a plea and partially as a call for introspection.

A3N: Returning to your new article, A Prescription for Healing a National Wound, how does Albert’s case further illustrate the US government’s mistreatment of the BPP? Conversely, how do you feel that Albert’s release would contribute to the healing of our nation?

AB: This case centers attention on the plight of the BPP at the hands of then FBI Director J.Edgar Hoover, who ran the FBI from 1924-1972 with unchecked authority and who ran the FBI without concern for the constitution or best practices. He ran the FBI as a personal enterprise to silence minorities, activists and anyone else who he could produce a reason not to like. Many times, his reasoning was not sound. He used his power to crush and silence people and he regularly violated the law in order to do so.

We, as a society, have never assessed the harm that flowed from this–the lives and careers that he wrongly destroyed; the current leaders who rode their way to the top doing what he groomed them to do and who have continued what he started; the impact that this had on activism and dissent in America; and the many people who lost their liberty as a result of his abuses of power. The Angola 3 case illuminates these concerns.

The Angola 3 case also brings attention to the growing problem of prosecutorial misconduct in this country and especially in Louisiana. Evidence was suppressed and testimony was induced. Inmates who initially denied knowledge of the murder changed testimony in exchange for favors. When asked about this under oath, state officials denied this, but proof now exists. Several courts have now concluded that grand jury discrimination was at play in Herman Wallace’s trial and also in Albert Woodfox’s trial. A grand juror who was married to a former Angola warden ended up serving on one of Albert’s grand juries and she actually brought a book she authored into deliberations, which contained negative overtures about the case.

Not only does this create a distrust for the judicial system, much of this created additional victims as some of the inmates whose testimony was “bought” were rewarded with freedom. Some of these criminals went on to commit additional crimes. The release of these criminals also re-victimized victims who were forced to live with the knowledge that the person who victimized them was back amongst them in society.

This case is a powerful educational tool for citizens who have thus far placed great faith in the words “convicted” or “a jury found him guilty.” Many people naively take these words at face value. For a large population of American citizens, convictions are obtained without any credible evidence. Many people, after seeing the “evidence” used against Albert Woodfox, now understand this point.

In Albert’s case, there was a bloody crime scene. It was one of the most ideal crime scenes imaginable because where else are fingerprints of every person on the property on file? None of the forensic evidence, including a bloody fingerprint found at the scene, matched Albert Woodfox or Herman Wallace. (See Woodfox v. Cain, 609 F.3d 774, 810 (5th Cir. La.), Jun 21, 2010). The authorities’ outrageous refusal to check this fingerprint against their own database of inmates’ fingerprints continues to this day. In 2008, NPR asked Louisiana Attorney General Buddy Caldwell why the state refuses to test the print. “A fingerprint can come from anywhere,” Caldwell explained. “We’re not going to be fooled by that.”

Albert even passed a polygraph test. In absence of any physical evidence, what was used against him was “bought” testimony from dangerous criminals, such as a legally blind man who, under oath, swore he saw things on the day of the murder, a robbery convict who was released in exchange for his testimony and then committed more robberies. This was done, not once, but twice. In Louisiana, state appellate courts signed off on this, not because of a conspiracy, but because of their design. When a criminal case is appealed, the court can’t revisit all the facts and evidence and act as a de facto jury. They must use standards of review and they are only allowed a narrow window into the case.

When insufficiency of evidence is raised in a criminal case, the state appellate court in Louisiana can only consider, in the light most favorable to the prosecution, if the record suggests any reasonable juror could have found the defendant guilty. Under this standard, it is rare to see a criminal case reversed on appeal. The state appellate process is much like a sniff test. They take a quick sniff then move on to the next one in line.

In Albert’s second trial, then Warden Henderson, while under oath, swore no incentives had been offered to the serial rapist, Hezekiah Brown, who they used to testify against Albert. The prosecutor stood before the court and praised this lying rapist. Specifically, he said he was proud of the lying rapist and he remarked that the lying rapist was courageous. This issue was brought up in an appeal before the federal court. That court agreed that this conduct was troubling, but no official action has ever been undertaken to address it.

This sets the stage for the next unsuspecting defendant to walk into the grips of the same cast of characters and the show begins all over again. Under a system that dispenses justice in this fashion, any one of us could be Albert Woodfox. That lesson is finally resonating.

Albert’s release could also highlight an ugly chapter in our history where the BPP is concerned. It could show the type of selfless work they did and the type of harm that came to many of them as a result. It could also aid in bringing an end to this era of social purgatory they have lived in and under since the 1960s.

In each of these contrasting ways, people will become informed then empathy and dialog will follow. These things lead to societal healing.

–Angola 3 News is an official project of the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3. Our website is www.angola3news.com, where we provide the latest news about the Angola 3. Additionally we are also creating our own media projects, which spotlight the issues central to the story of the Angola 3, like racism, repression, prisons, human rights, solitary confinement as torture, and more. Our articles and videos have been published by Alternet, Truthout, Counterpunch, Monthly Review, Z Magazine, Indymedia, and many others.