Abusing Prisoners Decreases Public Safety

–An interview with educator, author and former prisoner Shawn Griffith

By Angola 3 News

If given the attention it deserves, an important new book is certain to make significant contributions to the public discussions of US prison policy. The author, Shawn Griffith, was released last year from Florida’s prison system at the age of 41, after spending most of his life, almost 24 years, behind bars, including seven in solitary confinement.

Facing the US Prison Problem 2.3 Million Strong: An Ex-Con’s View of the Mistakes and the Solutionwas self-published just months after Griffith was released from what is the third largest state prison system in the US, after California and Texas.

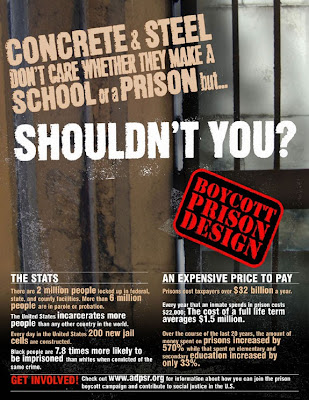

This new book’s thoughtful analysis and chilling reflections on what author Shawn Griffith experienced while incarcerated is a remarkable illustration of why the US public must listen to the voices of current and former prisoners who have stories that only they can tell. Griffith writes that “by integrating my own personal experiences with statistics and examples from different corrections systems around the nation, I am attempting to discredit the general perception that the system is designed to enforce and protect justice for everyone. The U.S. criminal justice system is an economically and politically profitable enterprise for special interest groups in this country. The general taxpayer needs to understand how the abusive policies fostered by these groups worsen the U.S. prison problem and the debt crisis through wasted corrections expenditures.”

Florida’s state prisons are the book’s main focus because “the majority of prisoners are incarcerated in state institutions. As of 2010, the US incarcerated 1,404,053 prisoners in state correctional institutions. For that reason, and based on my own twenty years of experience… Florida serves as an especially relevant test case for the changes needed in the US correctional system for two reasons. First is the size of Florida’s prison population and some of the political causes of its growth… Second, Florida has enacted some of the toughest sentencing laws of any state, causing correctional budgets to soar while educational budgets have been cut repeatedly,” writes Griffith.

After reading about the many different ways prisoners are abused, the very notion that US prisons are designed to rehabilitate or improve public safety, can only be viewed as a sick joke. Griffith writes that “hidden behind the walls, huge numbers of human beings have their spirits broken daily. Secretly, many suffer false disciplinary reports, illegitimate confiscation or destruction of personal property, physical beatings, rape, and sometimes fraudulent criminal penalties. Substandard nutrition, indifference to serious medical needs, and policies that encourage laziness have also become common. These practices help to sustain rates of recidivism, which is defined as a return to prison within three years of release.”

“Indeed, the strongest factor in reducing the rate of criminal recidivism is education, especially higher education, the one correctional expenditure that federal and state politicians have slashed. This course must be reversed,” writes Griffith, himself an example of the healing power of educational programs for prisoners. While incarcerated he began his long journey to full rehabilitation, gaining his GED and then taking over 40 accredited college correspondence courses with an emphasis on criminal justice, psychology, and marketing. He has a 3.5 GPA from Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. As a teacher in prison, he helped hundreds of inmates gain their GEDs.

Since his release in 2012, Griffith has lived in Sarasota, Florida where he founded Speak Out Publishing to publish other works of non-fiction that focus on tackling some of societies’ most pressing issues. Copies of

Facing the US Prison Problem 2.3 Million Strong can be purchased directly from Griffith, through his website:

www.speakoutpublishing.com, by mail: Speak Out Publishing, LLC at P.O. Box 50484 Sarasota, Florida 34232, or by phone: 941-330-5979.

Angola 3 News: You write that this book “isn’t just a commentary on correctional problems and solutions…it is also to share the human side of the story.” Based on your experience of spending almost 24 years in a Florida prison, what is the human side of this story?

Shawn Griffith: Sometimes I think people forget that prisoners and their families are people. The prisoners have committed crimes, but many of them come to prison with serious psychological issues, and they still have feelings like every person in this world. Most prisoners are not sociopaths, but instead human beings with more pain and trauma in their pasts than the average citizen. Committing crimes, for the most part, is a direct sign of their mental instability.

A good example was a murderer with the moniker, Arkansas. Arkansas was a real stand-up guy in prison. He was someone who kept his word, minded his own business, but had a violent father who instilled violent teachings into his head repeatedly during childhood. He would give a friend the shirt off of his back, but if you tried to harm him or get over on him, his training went into effect. He had some serious psychological issues that I saw him struggle with every day.

One day I walked into his cell and he had obviously been crying, although he tried to hide it. I asked him what was wrong, and he gave me the tough bravado treatment. But I have never given up easily, and after some coaxing, I learned that his mother was dying of cancer. Arkansas cleaned up his act immediately. He did everything by the book to get a hardship transfer closer to his dying mother, who was too sick to travel across the state of Florida.

After repeated attempts to get transferred, he gave up in total despair. His mother was the only person he had in this world. He turned his anger inward and sliced his wrists deeply. This got him transferred to the prison by his mom, since it had an Intensive Psychological Unit for suicidal inmates. This is the human aspect to which I refer. Neither Arkansas nor his poor mother should have had to deal with that in the only, heartless manner available.

Society should understand that 95% of prisoners will one day become their neighbors. Worsening people’s emotional trauma in this manner does nothing to increase these prisoners’ chances of becoming a productive, empathic citizen and neighbor. People should take an active part in reconsidering policies that ignore the human aspect of the story.

A3N: You argue that “what is most striking about” the abuse of prisoners “is how successful the government has been at maintaining the invisibility of it through ‘perception management.’ Public affairs offices work around the clock to spin damage control for correctional improprieties into non-controversial, politically correct sound bites. With 5,000 correctional jails and institutions dotting the U.S. landscape, prisoner abuses are common. However, much of the abuse is overlooked by unconcerned reporters who simply regurgitate government press releases.”

Combating this ‘invisibility’ by spotlighting the abuse of prisoners is critical for making prison authorities more publicly accountable. However, even on the rare occasion when the humans rights abuses inside US prisons are documented and presented to the general public, there is often still a widespread acceptance of these conditions because of a stigma against prisoners that causes much, if not most of the US public to feel that prisoners are ultimately ‘getting what they deserve.’ How can we better challenge this stigma? What role can independent media play?

SG: The primary challenge of media, whether radio, internet, or network, is ratings. Without positive ratings, popular media can’t sell advertisements. Considering that conventional media are already facing budget challenges as a result of new venues, particularly the internet, activist-style programming is not at the top of their agenda. Crime sells, but rehabilitation hardly brings in the ratings.

The goal of all media should be to interweave prison reform into popular crime programs, similar to the way Pat O’Connor does it at

www.crimemagazine.com. He understands the public mindset, and entertains his audience with titillating pieces on crime, yet does an amazing job of showing the crimes of the system in making recidivism worse. This should be the first method for all media, whether through traditional network programs or through today’s internet blogs.

The second challenge is to put public corrections officials’ feet to the fire. The only true national magazine that does this in the U.S. is

Prison Legal News. Many times I have personally witnessed mainstream media personnel come into a prison and print almost verbatim the perspective of guards or staff in the public-relations’ offices of many DOC central offices. Prison bureaucrats go to great lengths to cover improprieties. They know that if the public gets wind of how abhorrent conditions really are in most U.S. prisons, their jobs would be on the line. Thus, they only let in the media personnel who slavishly reprint their versions of public-interest stories. This is why many citizens share so many misconceptions about prisons, such as the common one that Florida’s prisons have air conditioning. It’s simply not true.

Media should reject such stifling of free speech by demanding to have less-restricted access to inmates, as they did in the late sixties and early seventies. Those prison officials that consequently restrict media access should then be lambasted with the truth, until they feel the heat, provide media access, and stop the abuses. Prisons are about prisoners, yet other than dramatized versions of prisons in shows like Lock-Up, rarely do people get the prisoners’ versions of conditions, until something extreme happens, such as killings of guards during riots. It shouldn’t have to reach that point.

There seems to be nothing independent about most mainstream media, at least not in dealing with prison issues, and that’s a shame in a country that supposedly prides itself on ‘free speech.’

A3N: If you were given five minutes on a mainstream news show, and were therefore able to speak directly to the general public, how would you address the commonly held belief that abusive prison conditions serve to reduce ‘crime’ and improve public safety?

SG: I would start with the ‘three Rs’: Retribution, Rehabilitation, and Recidivism.

A3N: Retribution?

SG: There is a fine line between retribution and correction. The best way to bring this home to people is to use the analogy of a child being taught to behave. For the reader, I would ask: “If you have an adopted child or even your own child who was mistreated in some way and maybe had a mental illness from some trauma in the past, would you try to fix that child by increasing the trauma further?” Of course not, unless you were an abusive parent.

Indeed, some people might have a difficult time relating a child’s misbehavior or need for a positive upbringing with a criminal. But the fact is that most prisoners have had some intense emotional trauma in their pasts, particularly sexual, physical, or emotional abuses during childhood. They act very similar to maladjusted children and most have not truly grown up. Research has repeatedly shown that prisoners have a very high rate of mental illness and also drug or alcohol dependencies.

Everyone understands the instinct for retribution. But that is the point; it is a primal instinct. Any society that bases its ‘corrections’ policies on instinct, rather than on scientific research, should not be shocked to see humans lash out like animals in response to further trauma resulting from societal retribution. Extreme punishment, and especially abuse, without a balance of love, creates rebellious, mentally-disturbed children. The public needs to understand that the same result, only ten times worse, occurs with prisoners subjected to punishment and abuse that does not have a balance of societal empathy. Any corrections policy must be balanced with both.

A3N: Rehabilitation?

SG: Social empathy is best implemented through the second “R” of Rehabilitation. Rehabilitation has gotten a bad rap, but true rehabilitation, as shown in the research statistics in my book, does work. It does reduce victimization and returns to prison.

This does not mean offenders should be treated with kid gloves or coddled. Instead, it means the prisoner should be viewed as a broken person who has little respect or belief in the law because abiding by the law has never coincided with that unbalanced person’s understanding of how to survive or deal with emotional problems.

The public at large has also been led to believe that the concept of rehabilitation has been discredited by scientific proof. That fallacy was responsible, in part, for the dismantling of prior reforms, especially in the South. The problem was not that rehabilitation did not work. There have been many effective examples that show that it does. Indeed, my own story serves as a relevant example of how rehabilitation can work. Rehabilitation has never truly been discredited. The problem is that it has not yet been properly and comprehensively implemented in most corrections systems.

I have offered a comprehensive program of solutions and rehabilitative policies in my book, ones that truly work, yet do you think anyone in corrections has called me to ask for help to implement these solutions? Not one person from any of the corrections systems in the fifty states has shown the slightest interest. Until society changes the general perception of what rehabilitation means, and how effective it can be when implemented properly, the U.S. prison problem will remain as it is.

A3N: Recidivism?

SG: This third ‘R’ is the indirect outcome of what society institutes. Right now the high rate of Recidivism in this country is a direct corollary to the corrections’ policies of this nation. As stated, retribution alone will create additional crime in an indirect way by worsening the inmate’s overall stability at the exact time when the stresses of release, bills, relationships, parenting, and other stressors fall upon the recently released felon.

From 1970-2010, the rate of incarceration in the U.S. increased over 1,000%. In April of 2011, a Pew Research Center report showed that we still had a recidivism rate of 43.3%—on data compiled from 2004 to 2007—showing the need for more improvement. Retribution, or the “Lock-em up, and throw away the key” application of corrections has failed miserably.

A3N: You write: “As disturbing as this may sound, politicians and the bureaucrats who control the system have no incentive to reduce recidivism. To the former, passing tougher sentencing laws increases campaign dollars from prison construction companies, private corrections corporations, and law enforcement unions. To the latter, making policies that encourage prisoners’ ignorance and laziness ensures they will remain unemployable and increases their chances of returning to prison. More recidivism equals more prisons; more prisons equal more job security for prison guards and private corporations; more prison guards equal more members for correctional officer unions; and, more members and private profits equal increased campaign donations to the tough-on-crime politicians who cater to them. This is the main reason that Florida has one of the largest prison populations in the country, not an increasing crime rate. The same applies to the overall nation.” With this in mind, what alternative solutions do you suggest to lower recidivism rates and improve public safety in a practical way?

SG: After years of contemplation, these are some of the primary solutions that I propose would decrease recidivism and increase public safety. However, hundreds of solutions are provided throughout the book:

- Pursue criminal justice sentencing reforms that place ceilings on sentences, increase judges’ discretion to make downward departures, increase drug treatment and other community corrections alternatives, and abolish minimum-mandatory provisions for non-violent offenses.

- Pursue policies of prisoner placement that reduce current intrastate distances from families by forty percent and completely abolish non-voluntary interstate placements. This would then be followed by increased contact between families and offenders at visitation. This has been shown to reduce the unnecessary burdens placed upon family ties, especially between children and prisoner parents, thus reducing intergenerational crime and recidivism simultaneously.

- Pursue the reversal of corrections policies that diminish prisoners’ familial contact for disciplinary purposes, increase normal contact visitation, and establish a comprehensive private healthcare plan to augment Medicaid for children of prisoners.

- Lobby legislators to pass laws that reverse pen-pal and religious-correspondence restrictions and other policies of isolation, while instituting other safeguards to ensure societal and penalogical security.

- Seek the abolishment of policies that charge co-payments, reimbursements, and other double-taxation charges to prisoners’ taxpaying loved ones. This would include the pursuit of fair collect-call rates and profit margins on the commercial resale of all goods and services to prisoners and their families, since the families pay for both.

- Pursue programs of inexpensive electronic video communications between prisoners and their children that apply to both genders of all incarcerated parents.

- Seek increases in rehabilitative activities such as music, artwork, writing, and hobby craft that can be leveraged to reduce solitary confinement and visitation restrictions as positive behavioral incentives.

- Present the statistics in support of increased drug and alcohol treatment programs and make early release credits dependent on successful participatory recovery.

- Lobby state and federal leaders to institute mandatory GED classes and increased vocational and higher educational opportunities for prisoners. Reverse the laws of the 1996 prohibition against prisoners using the Pell Grant for accredited college correspondence courses.

- Implement agricultural, industrial, and service economies that increase training and financial incentives inside the prisons, and teach personal responsibility for the expense of living and child support while incarcerated. Accompany this with the establishment of a Corrections Risk Factor (CRF) to employers of prisoners to provide a mathematical wage rate that is fair for both prisoners and the companies that hire or compete in the same industry. This would prevent the prior examples of private companies exploiting prisoners for their labor, and unfair competitive practices against companies that don’t hire convicts. The increased work ethic in prisoners would decrease the burden on taxpayers through a reduction in recidivism and correction expenditures.

A3N: An article you wrote for Crime Magazine criticized the use of solitary confinement in US jails and prisons. In what ways does the practice of solitary confinement influence recidivism and public safety?

SG: In fact, experts on solitary confinement have documented the effects of long-term solitary confinement to include PTSD, increased risk of suicide, insomnia, paranoia, uncontrollable feelings of rage, and visual & auditory hallucinations. Literally thousands of prisoners are released directly into U.S. society from these confinement cells every day. Instead of being exposed to rehabilitative programs while in prison, many have been subjected to the cruelty of solitary confinement and have turned into walking time bombs. They are then released into society with $50 and a bus ticket, and kicked out the door mad and emotionally disturbed.

Maybe the practice of using solitary confinement would be more tolerable if there were no alternatives. To the contrary, there are a number of positive, rehabilitative incentives that could be used to replace most of our dependency on solitary to control behavior. For instance, music programs, drug rehab, hobby-craft, and incentivized jobs could all be used to reduce violence and misbehavior. From 1990 to 2010, these programs were slashed, as the push for longer sentences became commonplace. With longer sentences came the need to build more and more prisons. This in turn created incentive to shift money away from rehabilitative programs, which then created the demand for solitary confinement units.

Without ordinary rehabilitative incentives at their disposal, prison administrators had little else to use for controlling prisoners’ behavior. The policy became one of suppression and debilitation at any cost, and the cost has been incalculable.

A3N: Further illustrating ‘the human side of the story,’ cited at the beginning of our interview, your book examines another under-reported story: how prison policies affect the families of prisoners. To conclude our interview, why do you argue that it is the children of prisoners who suffer the most?

SG: For starters, a policy increasing a financial burden just slightly can and does trigger the decision by some desperate mothers to give their children up to foster care. With their delinquency worsened by the absence of the imprisoned parent, many of these children end up going to juvenile detention centers. This is especially true for those who are unable to partake in contact visitation with their mothers and fathers because of the distance that separates them. Fathers are typically housed an average of 100 miles away and mothers an average of 160 miles away from their children.

Over half of all incarcerated parents reported having never received a personal visit from their children. Much literature on the developmental effects of separation from a primary caregiver has been produced. In one report issued by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 66% of incarcerated mothers and 40% of incarcerated fathers reported being one of the primary caregivers prior to incarceration. The Urban Institute also showed in a study that there are specific character and behavioral traits in children that are directly affected by parent-child separation, especially complete separations that preclude contact visits.

These traits include, among others: feelings of shame, poor school performance, increased delinquency, loss of financial and emotional support, increased risk of abuse by new caregiver(s), impaired ability to cope with future stress and trauma, disruption of normal developmental progress, increased dependency and maturational regression, and intergenerational patterns of criminal behaviors.

These findings are made even more troubling when the age of these children is revealed. In prior studies, 56% were shown to be between one and nine years of age. An additional 28% of them were under the age of fifteen.

A3N: Keep up the good work, Shawn! Because your book examines such a wide range of topics, our interview has only been able to scratch the surface. To read it for themselves, and to support your work as an author and self-publisher, we encourage our readers to get a copy of Facing the US Prison Problem 2.3 Million Strong

, purchased directly from you, by internet: www.speakoutpublishing.com, by mail: Speak Out Publishing, LLC at P.O. Box 50484 Sarasota, Florida 34232, or by phone: 941-330-5979.

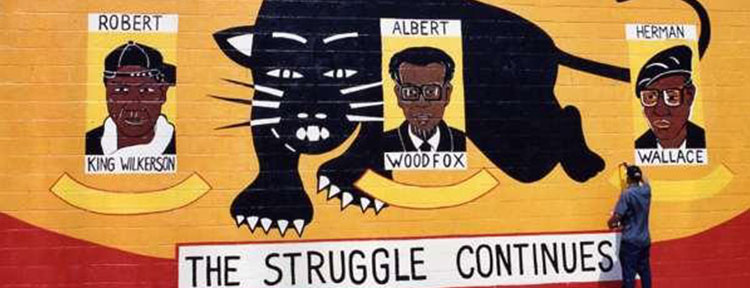

–Angola 3 News is a project of the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3. Our website is www.angola3news.com where we provide the latest news about the Angola 3. We are also creating our own media projects, which spotlight the issues central to the story of the Angola 3, like racism, repression, prisons, human rights, solitary confinement as torture, and more.